In the summer of 1816, Andrew Molloney returned home to his house in Dame court, Dublin to find himself locked out. Resigned to the fact he was going to have to sleep out, he went to find a spot in the street. There he encountered three women Mary Doyle, Mary McQuead and Mary Harvey. A later court case seems to have implied the women may have been prostitutes as Molloney explicitly testified he had “no acquaintance or freedom with them“. According to his testimony he rolled up his coat to use as a pillow and fell asleep.

When he woke in the morning he found he had been robbed of £13, a substantial amount of money at the time. He accused the three women who were subsequently taken before a court. William Connor of Exchequer street and owner of a shop gave crucial evidence, when he testified that the women had given him £10 on that very night.

Freeman’s Journal, September 2nd, 1816

Unsurprisingly the women were found guilty and sentenced to one years hard labour in Smithfield House of Correction. However so bad was the reputation of the House of Correction in Smithfield at the time that Mary Doyle pleaded with the judge to change her sentence and

“make her punishment seven years transportation and expressed great horror at going to the House of Correction”.

(Transportation was in effect permanent exile and seven years of labour, 14,000 miles away in Australia.)

When the judge refused her pleas, Mary appears to have been enraged. The reporter of the Freeman’s Journal continued his report

“she changed her style of supplication to the most faring kind of defiance and abuse“

Sadly this did not help Mary’s case; she was sent to the feared House of Correction and put in solitary confinement. Unfortunately the reports from the time do not tell us why exactly the House of Correction was so feared. However the fact that Mary Doyle would choose exile on what was known as the fatal shore instead, is indicative of its reputation

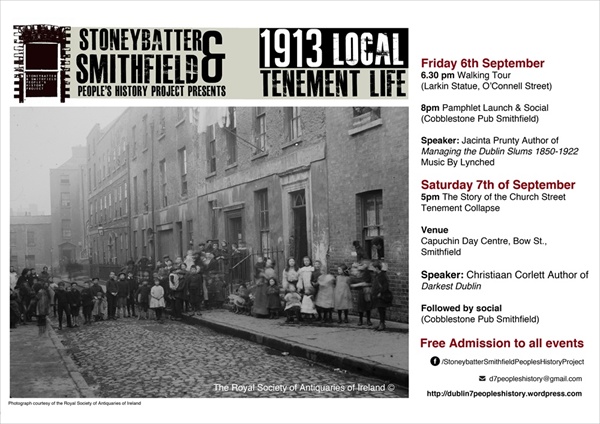

If you want to hear more about the history of prisons and female prisoners like Mary Doyle come to our free public meeting this Saturday (October 5th) at 5 p.m. in the Cobblestone pub Smithfield titled

“The Grangegorman Depot and the transportation of Irish convict women to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) 1840-1852.” Find out more details here

By Fin Dwyer